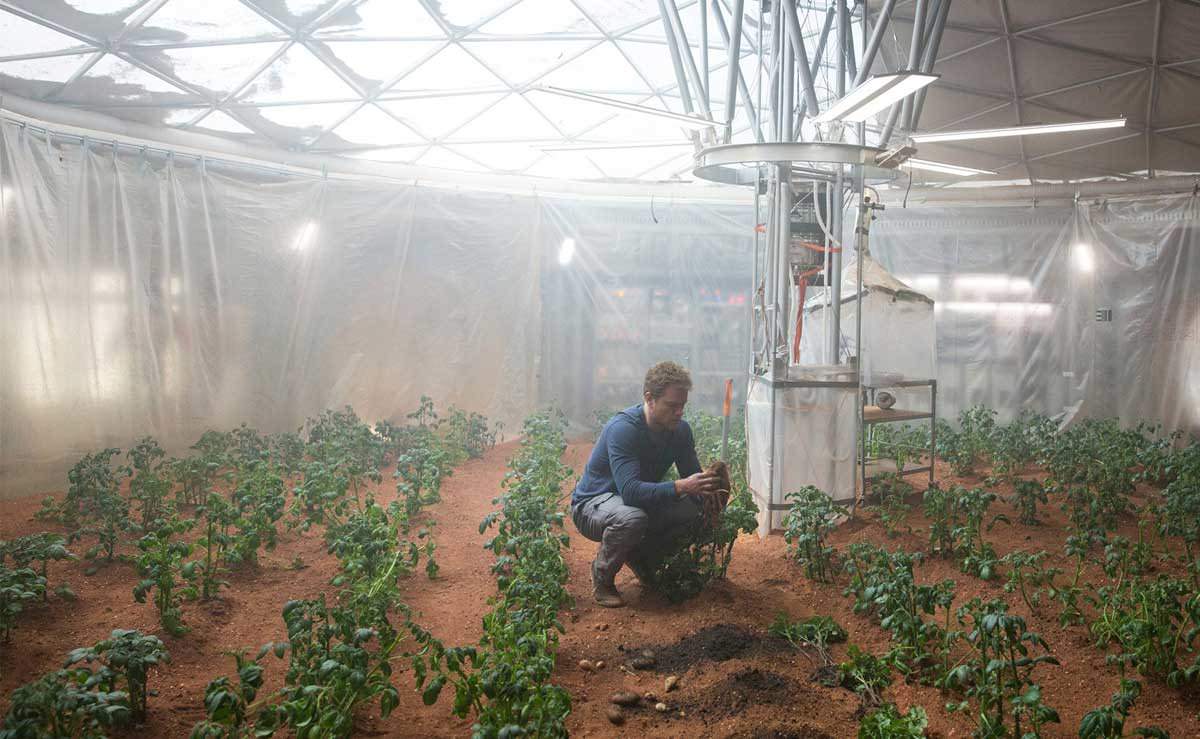

In the movie “The Martian”, Matt Damon is left alone on Mars and has to plant potatoes to survive. Though we all hope real astronauts will never have the same traumatic experience as his character, Dr. Watney, there is no doubt that if we are to guarantee the sustainability of future human missions to other celestial bodies, such as the planets of the solar system or the Moon, we must learn to produce a large part of the resources required on site, as in Ridley Scott’s movie.

This is the concern of ReBUS (In-Situ Resource Bio-Utilization for supporting life in Space), the project begun in response to a call for tenders announced by the Italian Space Agency (ASI) and presented on November 18 following the first two years of work.

In addition to Telespazio, ReBUS involves a number of Italian universities and research centres, such as Federico II University of Naples, which is coordinating the project, Pavia University, Tor Vergata University of Rome, the National Agency for New Technologies and Economic Development (ENEA), the National Research Council (CNR), the Istituto Superiore di Sanità (Italian National Institute of Health) and two of Italy’s biggest aerospace companies, Thales Alenia Space Italia and Kayser Italia.

ReBUS is inspired by the awareness that long-term missions to the Moon and other planets in our solar system must necessarily produce at least some of the resources necessary for life, such as oxygen, water and food, in situ. At the moment, the principal human outpost in Space – the International Space Station (ISS) – is served regularly by cargo capsules bringing the astronauts on board all the supplies they need.

But human missions to other planets would be so far away that this would become very complicated.

In the case of the ISS, loss of a single cargo shuttle is a serious but solvable problem, but for a mission to another planet, the absence of supplies could put the astronauts in serious danger, with increasingly scarce supplies.

Hence the importance of plants: they not only represent a source of food, but convert wastes into resources, triggering a virtuous circle of independent production.

A scene from 'The Martian', with Matt Damon growing potatoes on Martian soil. Courtesy of 20th Century Fox

But reality is more complicated than it would appear in “The Martian”, and there are still many unsolved problems with plant cultivation away from Earth.

It is not entirely clear, for example, just what role gravity plays in plant growth and how this would be altered in space, or how plants might react to ionising radiation, which is screened out by Earth’s magnetic field so that only a minimal amount reaches our planet. Nor is it clear what the impact of a different day/night cycle might be for plant growth, or the ability of plants to adapt to different soils and substrates – like those on the Moon or Mars, where of course there is no organic component and there may be substances such as perchlorates which, if absorbed by the plants, would be toxic to humans.

In search of answers to these open questions, the ReBUS consortium is focusing on three main areas of study, each with its own specific goal.

The first line of study involves identification of the best species for cultivation away from the planet Earth, understanding the effects of adverse environmental conditions on other planets and identifying the type of soil, fertiliser and cultivation strategies most appropriate for their growth.

At the same time, the ReBUS project studies methods and techniques for creating appropriate fertilisers and soils from waste materials produced directly on site, such as food scraps and organic human waste, using microorganisms, alone or in combination, as consortia of bacteria, fungi, and even insects and cyanobacteria, which are organisms capable of surviving and multiplying in extreme environments.

Lastly, special attention is being paid to analysis of the quality and safety of the food produced and its effects on the astronauts’ health.

Producing food in a future base on the Moon or Mars is a challenge that still presents many unknowns, which is why the International Space Station and, in the future, the Moon Gateway offer vast potential for studying how plants behave in environments other than Earth.

This is why ReBUS aims to follow up on the study by suggesting a number of new experiments to be performed directly in orbit or on the Moon. At present, the many proposals include the possibility of cultivating particular varieties of edible plants on board the ISS or using soil from the Moon in one of the European Lunar Lander’s first missions, one of the first programmes likely to benefit from the communication and positioning services offered by Moonlight.

Telespazio, with decades of experience preparing and conducting experiments on board the ISS and other microgravitational platforms, is ready to help the consortium outline and implement the subsequent phases in the project, so that one day astronauts may, perhaps, really be able to eat potatoes grown on Mars.

Just like Matt Damon in Ridley Scott’s movie!